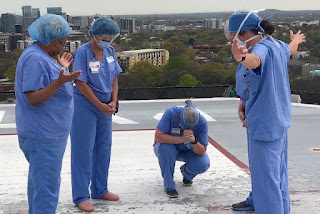

Nurses awaiting helicopter, FaceBook

The current

coronavirus pandemic certainly has given all of us around the world a focus and

heightened appreciation for all of our caregivers in a multitude of specialties. And in this time of world-wide digital

communication we’re now in close touch with those on the battle fields fighting

for those stricken with the virus. Some

of them are saying that those that stay at home and do not facilitate the

movement of the virus are on the front lines and that they are behind the lines

caring for the patients that are seeking medical treatment.

Observing this

crisis unfold called to mind a response of the famous anthropologist Margaret

Mead when a student asked what she considered to be the first sign of

civilization in a culture. Excavations

of ancient sites have uncovered the remains of fire pits, flint stones used for

hunting and tools, clay shards, etc. But

she didn’t use any of these common examples.

Instead she replied that it was a healed thigh bone. She explained that in evolving cultures a

broken leg was a certain death sentence in the animal world. “Helping someone through a time of crisis is

where civilization starts”, she concluded.

Heroes aren’t

born. They’re created in times of strife

and struggle. We humans are hardwired

for empathy. And research has noted that

when we observe others suffering, our brains are stimulated so that we

experience the pain ourselves.

There’s a great

void between empathy and apathy. People

seem to have a range within which we can nurture either trait. Learning new skills will grow parts of our

brain for instance. Practicing

generosity, concern for strangers and others’ emotions grows our ability to

create a kinder world. And empathy is

primary in the caregiving profession. I

still remember a senior ICU nurse that came into my room around midnight after

major surgery and talked for quite a while to assure me that everything would

be OK.

But full time caring

for the sick and being witness to dying patients will take a toll on our

caregivers, demanding our own empathy for them.

I was witness to friends when the husband was terminally ill and

required a demanding amount of time and energy from his wife. She actually passed away before him. And our oncologist that worked tirelessly

with my wife to seek treatments for her metastasized breast cancer was said to

have a terrible bedside manner and lack of empathy. Once we spent time understanding his world,

we came to realize that we too would have to emotionally detach ourselves from

multiple patients with critical diseases for our own sanity. Nevertheless, when the end was near, he still

revealed his underlying humanity we had appreciated all along and for which I was

grateful.

No comments:

Post a Comment